International Shale Gas & Climate Change (Reimagine Energy Policy: Part 3 of 4) [Gaille Energy Blog Issue 35]

- Posted by scottgaille

- On October 3, 2016

- 0 Comments

“The U.S. leads the world in reducing carbon emissions for the most recent 5- and 10-year periods. Over the past 5 years U.S. carbon dioxide emissions have fallen by 270 million tons.” – Forbes

Spinning windmills and glistening solar panels—that’s what we envision when we read about CO2 reduction. Shale gas does not usually come to mind. Yet it’s the next best thing. Gas emits half as much CO2 as coal-fired electricity generation:

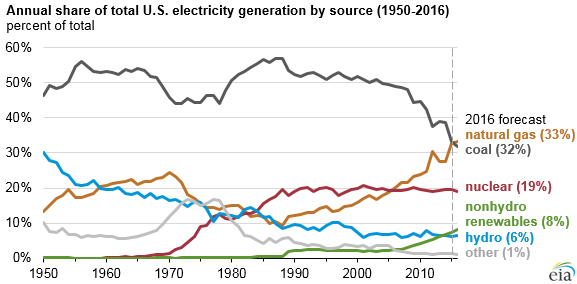

American gas production has surged as a consequence of shale development. The practical result of abundant, cheap natural gas is a reduction in reliance on coal. Prior to shale, coal generated more than half of America’s electricity. Coal’s contribution has since plummeted by ~20 percentage points—15 of which are attributable to shale gas and only 5 to renewables.

The rest of the world has not followed America’s example of reducing carbon emissions: “Over the most recent 5-year period, China led the world with a 1.1 billion ton increase. India was in 2nd place with a 540 million ton increase” (Forbes).

This divergence is being driven by other nations’ continued reliance on coal to generate electricity. For example, China utilizes coal for about two-thirds of its electricity generation:

Paradoxically, China has the largest shale gas reserves in the world—50% more shale gas than the United States. To its southwest, India and Pakistan also have considerable shale resources, each sitting atop ~100 TCF. As the figure below illustrates, shale gas is truly a global resource:

I spoke at the Asia Shale Conference in Shanghai last year, addressing questions about why shale development has languished in China and elsewhere. The slow pace of international shale is attributed to many factors—including political risk, poor fiscal/tax regimes, absence of private mineral rights, shortages of drilling rigs and frac crews, lack of water, and/or poor pipeline infrastructure.

There already is an American energy policy in place to help other nations overcome such obstacles. As I explained in the Energy Law Journal: “The United States government has sought to . . . actively support[] international shale. Reasons for the policy include ‘part of a broader push to fight climate change, boost global energy supply, and undercut the power of adversaries such as Russia that use their energy resources as a cudgel.’ For example, the U.S. State Department’s Unconventional Gas Technical Engagement Program (UGTEP) seeks to ‘establish[] the right regulatory policy and fiscal structures’ for shale gas development.” Unfortunately, the State Department’s efforts have not met with much success. While the United States has drilled more than 60,000 shale wells, the tally for the rest of the world stands at ~1,000.

In order to better understand this divergence, it’s important to look at what actually happened in Texas’ Eagle Ford shale. ~350 different companies drilled ~15,000 shale wells. One third of these were drilled by ~320 smaller companies, names most of us would not recognize. The successful ones then sold their stakes onward to ~30 larger companies, which consolidated the best acreage and executed widespread development drilling. It’s precisely such intense “trial-and-error” by hundreds of smaller companies that made American shale so successful.

Why are 350 companies drilling wells in the USA and a just handful anywhere else? The United States is the only nation in the world where mineral rights are predominately private. A small driller can approach a rancher in Texas, quickly sign-up a lease and spud a well, risking little capital beyond the drilling cost. Elsewhere, mineral rights are owned and licensed by the government. Other nations typically require operators to meet rigorous prequalification criteria, eliminating all but the largest companies. Governments also expect eight or nine figure signing bonuses before drilling even commences.

All of this is a recipe for less activity. International shale is being smothered by bad energy law. While it’s unrealistic to expect countries like China to adopt private mineral rights, it’s possible to design a synthetic version—one that creates incentives similar to those in America. A special shale gas concession might have the following key terms and conditions:

- Direct Negotiations (no bid rounds, as auctions increase the risk for smaller companies since they require considerable expenditures on data, study, and prequalification before a license is obtained)

- No Up-Front Bonus (eliminating the signing bonus decreases the risk for investors and enables capital to be focused on drilling)

- Minimum Work Program of One Well per Year (this lower threshold will increase the number of companies participating)

- Only Penalty for Failure to Drill Is Loss of License (no requirement of letter of credit guaranteeing the one well)

- Each Well Earns Option of a One-Year Extension (companies can hold the acreage for another year and continue to drill)

- Small Concession Size of 500 sq. km. (125,000 acres) (smaller licenses enable many companies to engage in trial-and-error drilling in closer proximity to one another)

By lowering the barriers, costs, and risks for smaller companies, more international shale wells will be drilled. Over time, services and infrastructure will follow, leading to more productivity—and ultimately, lower carbon emissions.

The purpose of my Reimagine Energy talks is to discuss ideas for improving energy policy that could be supported by both Democrats and Republicans. What good is the Democrats’ goal of zero carbon emissions if other nations’ emissions continue to surge? Republicans also should be supportive because international shale development will utilize American technology and know-how, leading to more jobs in our own energy sector. The forthcoming and last installment in the Reimagine Energy series will tackle the challenging issue of how the United States can influence other nations’ energy policies.

About the Gaille Energy Blog. The Gaille Energy Blog discusses issues in the field of energy law, with weekly posts at http://www.gaillelaw.com. Scott Gaille is a Lecturer in Law at the University of Chicago Law School, an Adjunct Professor in Management at Rice University’s Graduate School of Business, and the author of two books on energy law (Shale Energy Development and International Energy Development).

0 Comments